Flying on a plane has somehow taken a step-down from its pre-pandemic ‘elegance’ to its current state as a post-apocalyptic dystopian thriller. Passengers are fighting with airplane crews and each other, and it is all caught on video. Explanations of this phenomenon have focused on contention around mask mandates and the stresses and isolation of the pandemic engendering anti-social behavior in people who are being released back into society. But, there is a chance that these people aren’t as crazy as they seem, they could be economically rational creatures defending their private property.1

After the US airline bailouts of the pandemic, taxpayers should be forgiven for treating commercial airlines as their private property. US airlines took an abusive amount of money from taxpayers during the pandemic, most of which they didn’t need and don’t have to pay back2, and when tax-payers returned to ‘the friendly skies’, they were greeted with the same terrible dehumanizing service as before.

Over the last 100 years, the attitude of the US Government towards economic downturns has shifted from posting signage that reads ‘Play at Your Own Risk’ to baby-proofing the entire house, and padding every edge of every table. The overreactions we see today have their roots in the Great Depression, because those fighting the cyclicality of the economy are singly focused on how to avoid The Great Depression of the 1930s and don’t appreciate that the next Great Depression could take a different shape.

The Great Depression:

The Great depression began in 1929 and lasted 10 years. At its peak, US GDP fell ~30% and unemployment reached ~25%. To put this into context, during the 2007-2009 recession, US GDP fell ~4.3% and unemployment reached ~10%. In 1929, after the stock market crash, consumer demand for goods in the economy collapsed. Prices and wages deflated. As the public lost confidence, they started hoarding money and taking it out of banks. When people withdrew their money from banks, banks failed. Those who had not taken their money out of failed banks lost their entire savings. This led to more people taking more money out of banks, which led to more bank failures. To make matters worse, it appears as though the entire world was in black and white, and no one seems to think that was strange.

Economists have spent nearly 100 years learning from this specific period and trying to prevent its recurrence. Two schools of thought have emerged on how to avoid and treat economic downturns.

The first was from John Maynard Keynes, who is referred to by his first, middle, and last name even though he was not a presidential assassin. During the depression, Keynes proposed countercyclical spending by governments to support employment and help jump-start the economy. To fund this spending when times were bad, governments would use budget deficits. Keynes’ countercyclical government spending is best expressed by the government work programs of the 1930s, under FDR’s New Deal.

In 1963, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz wrote ‘A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960’. While the title of the book was largely metaphorical, it was about the monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960. They argue that the Federal Reserve Board’s (the Fed) unwillingness to cut interest rates in a timely manner caused the Great Depression.

In 1929, the Fed increased interest rates to fight increased speculation in the stock market and caused the ensuing market crash. Their analysis shows that the Depression was caused by a contraction in the supply of money which they blamed on the inaction of central bankers and the rigidity of the Gold Standard. After the death of Benjamin Strong, Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, there was a power vacuum at the Fed. Under the leadership of George Harrison and the influence of Fed Governor Adolf Miller, the Fed acted too timidly during the depression. They favored allowing nature to take its course and punishing those who took too much risk when they should have actively lowered interest rates to fight the Depression.

Finally, they hypothesize that had Benjamin Strong not died in 1928, before the forthcoming depression, the Fed would have had someone in leadership with the will to lower interest rates in a timely manner. The popularity of blaming George Harrison and Adolf Miller is widely accepted, and it is not coincidental that you don’t see any economists named Adolf after this time period.

Policy makers who study the depression come away with two tools for fighting the cyclicality of the economy. Due to the Keynesian influence, government-elected officials learn that they should run large deficits during times of economic hardship. This is referred to as the Fiscal Policy tool. Due to Friedman and Schwartz’s influence, central bankers learn that they should lower interest rates during times of economic hardships to make money more available. This is referred to as the Monetary Policy tool.

While Monetary and Fiscal Policy are powerful tools, they unfortunately rest in the hands of central bankers and elected officials, who themselves are powerful tools. While in their purest form these policy tools can be used to help lessen the impacts of downturns in the economy, they can also be abused by those that control them. Elected officials can use Fiscal Policy during times when it is not necessary, to carry favor with voters and boost prospects for reelection. Central bankers can use Monetary Policy at times when it is not needed to attain goals that are outside of their mandate.

The Fed has a dual mandate: to promote maximum employment while keeping prices stable. Lower interest rates reduce unemployment because when credit is more readily available, it is easier for businesses to form or expand operations and hire more people. At the same time, it stimulates consumer spending by making purchases through credit easier. However, if the Fed keeps rates too low for too long, there is too much money in the system chasing the same amount of goods. This causes price levels to rise, also called inflation, because the supply of money has increased, making every dollar less valuable than before.

While interest rates are like a cup of coffee to the economy, they are like crack cocaine to the stock market. The impact on stocks from low interest rates is two-fold. First, they boost the overall economy, which is positive for most companies. Second, by lowering interest rates, the government lowers the yields on less risky government securities. As a result, investors look to riskier assets, like the equity market, to get the same yield they were previously able to get from less risky assets. Therefore, low interest rates can lead to stock market and asset bubbles.

Of course fiscal and monetary tools are abused. This leads to deficit spending and low interest rates even during times of economic prosperity.

There is an important lesson from the depression that is often left out. How to avoid the events that led up to the stock market crash.

Montagu Norman was Benjamin Strong’s Greatest Weakness:

Starting in the late 1800s, world currency was dominated by the Gold Standard. Under this system, each country had its currency fixed to the amount of gold in its bank at a set conversion rate. For every dollar of currency, there was a corresponding bar of gold in the bank. Governments could not issue money if they did not have the corresponding gold. Contrast that with today, where governments are limited in the amount of currency they can issue only by the amount of ink in their printing presses.

Following WW1, the US was in a strong economic position. The US only participated in the last half of the war and had therefore incurred less expense and destruction than others. The European allies had borrowed heavily from the US during the war to finance their operations and were dependent on exports from the US, because industries in Europe had been devasted from the fighting. Under the Gold Standard, this meant that significant amounts of gold moved from Europe to the US.

During the war, due to the lack of gold in its bank, England faced a currency crisis and had to unofficially leave the Gold Standard. After the war, Montagu Norman, Governor of the Bank of England, was determined not only to return to the Gold Standard, but also to do so at England’s pre-war gold conversion rate. Prior to the war, England had been the main banking hub of the world and returning to gold at its pre-war rate was a matter of national pride.4

In order to return to gold at a conversion rate that was higher than their reserves of gold would allow, England needed more gold. Luckily for England, Montagu Norman was best friends with Benjamin Strong.

Both 50-year-old bachelors with similar jobs, Strong and Norman had a lot in common. Strong suffered for his adult life with Tuberculosis, while Norman had periodic fits of ‘nervous exhaustion’. It is worth noting how strange it is that the English, famous for their stoicism, chose the one person on the island who got panic attacks to lead their central bank.

Strong and Norman had a whirlwind bromance that began when they met in 1921. They would see each other twice a year for the rest of Strong’s life3, and this was at a time when they couldn’t jump on a plane, watch a passenger go a few rounds with a flight attendant, and then land in Heathrow in 6 hours. It took 5 days to cross the Atlantic on an ocean liner at the time.

Under the Gold Standard, Britain needed to attract more investment from abroad to increase its gold reserves. This could be done by either increasing interest rates in England, or somehow decreasing interest rates abroad, giving England a relatively higher interest rate to attract foreign currency and gold. The prospect of increasing interest rates in England was challenging, the economy was still struggling from the war, and rising interest rates would increase unemployment. Prospects for lowering interest rates in the US were better. The US was in the midst of a mild recession.

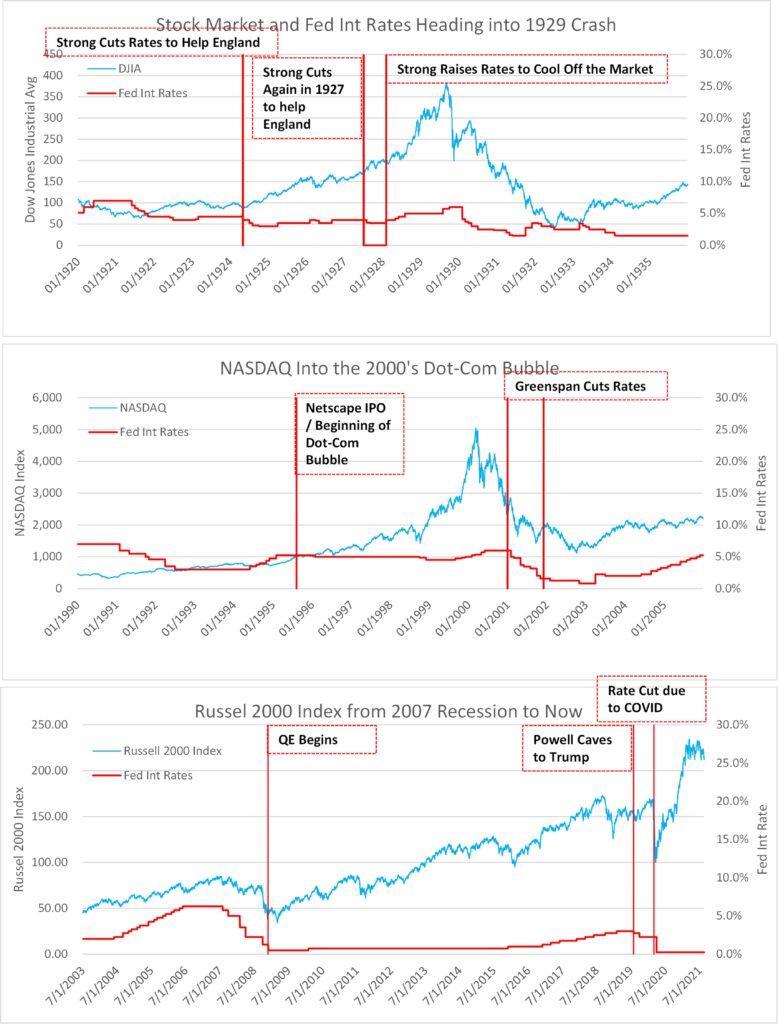

Strong was happy to help. From May to August 1924, Strong reduced US rates 3 times, from 4.5% to 3.0%. In September 1924, the US stock market began its 5-year bull run that culminated in the Crash of Oct 1929.

Back over in England, Norman convinced Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, to announce the return of England to the Gold Standard. In May 1925, Churchill officially confirmed the return of England to the Gold Standard with the passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1925. And all was well, England was back on Gold at its pre-war conversion rate.

But England’s pre-war conversion rate turned out to be too high, and in 1927, England was back in a deflationary crisis. Benjamin Strong, who was becoming increasingly autocratic on the Fed, came to the rescue again. Over the objections of half the board, and the resignation in protest of the Chairman of the Fed, Strong pressured the Fed to cut interest rates 0.5% in July 1927.

Since the Fed’s first rate cut in 1924 to its cut in July 1927, the stock market5 was up ~70.5%. After the July 1927 rate cut, the market really started to move, increasing another 20% by February 1928. By then, the Fed realized they had kept rates too low for too long and started to increase rates, but it was too late. After the Feb 1928 rate increase, the market went up another 85% in the next 19 months, until the crash of October 1929. From the time the Fed cut rates in Sep 1924 to the Crash of Oct 1929 the markets increased ~250%.

The Dot-Com Bubble of 2000/2001 We are Still Paying for:

If you thought that the AOL CD-ROMs on the counter of every Blockbuster were free, think again. The economy has been paying for them over the last 20 years. In 2000, the popularity of investing in tech companies got ahead of itself. The internet was coming and people knew it would be big, but most hadn’t figured out how to make money from it yet. Many tech companies IPO’d in the 1990s before turning profitable, under the assumption they could ‘fake it till they make it’.

From the Netscape IPO in Aug 1995 to the peak of the Tech Bubble in Mar 2000, the NASDAQ went up ~410%. After its peak, the NASDAQ fell ~70% over the next year, not regaining its 2000 peak until 2015. Tech companies eventually figured out how to make money, by tracking users’ internet activity and selling it to advertisers… which brings us to this article’s sponsor.6

In March 2001, the US entered a mild 8-month recession driven by the bursting of the tech bubble, increased unemployment (which was buoyed ironically when computers didn’t melt down on Jan 1, 2000 ruining the cottage industry that had sprung up to fight the Y2K computer crisis), and the Sept 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

The 2001 recession was short and mild because then Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan followed the playbook of Monetary Tools and began cutting rates in Jan 2001. From Jan to Dec 2001, the Fed cut rates7 11 times from 6.5% to 1.75%. Thanks to Greenspan’s quick action, the tech bubble recession was kept from spiraling out of control, and we never had to worry about anything like that again.

However, even though the recession was over by December 2001, Greenspan kept rates below 2% until November 2004. Keeping rates low after the economic threats of the dot-com bubble subsided had two effects. Cheap credit allowed consumers greater access to credit markets which enabled them to afford assets that had previously been financially out of reach. At the same time, low interest rates left investors searching for investment vehicles that would pay higher interest rates. In a low interest rate environment, investors had to accept more risk to achieve the same yield as before.

These factors, when joined together, combined to form the supply and demand for sub-prime mortgages. Sub-prime mortgages gave consumers access to the assets they desired, while also providing investors with an oasis of yield in a desert of low interest rates. This win-win love affair led to the subprime mortgage crisis and recession of 2007-2009.

In the aftermath of the recession, Alan Greenspan’s legacy has been tarnished. The two main areas of criticism against him are that he failed to regulate the housing market, and that he kept rates too low for too long after the 2001 dot-com bubble burst. Most importantly, now that we have learned these lessons, we will never repeat them again.

Quantitative Easing: A Clear Form of Cultural Appropriation

In the 2006 song “Make it Rain” by Fat Joe and Lil Wayne, Lil Wayne sings “I make it rain, I make it rain, I make it rain on these hoes”. Through the heavy use of context clues, ‘making it rain’ in this situation means to throw money haphazardly into the air at a strip club and enjoy the chaos and temporary popularity that ensues.

In Response to the subprime Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke made like a good Fed Chairman and cut rates from August 2007 to Dec 2008 from 5.25% to 0.00%.

Pop quiz hot shot: you are the Chairman of the US Federal Reserve. You are facing a financial crisis. You just lowered interest rates to zero and unemployment is still rising. What do you do?8

Ben Bernanke asked himself this question in the fall of 2008, as he paced back and forth nervously in his office. Taking a moment away from the crisis, Bernanke decided to escape with his one secret indulgence: 2000s rap music. He pulled out his Microsoft Zune,9 and in a nostalgic mood for a better time, played his summer 2006 mix. When Lil Wayne’s ‘Make it Rain’ came on, the solution came to him. He would make it rain, he would make it rain on all of us hoes, and he would do it by Quantitative Easing (QE).

Traditionally, when the Fed lowers interest rates, they do so by buying US Treasuries on the open market. When treasuries are purchased, the yield that investors demand in return for owning Treasuries is reduced. The more Treasuries the Fed buys, the lower interest rates go. Under QE, the Fed moves from buying US Treasuries to buying riskier securities, like the mortgage-backed securities at the heart of the financial crisis. This allows bankers to increase the money available in the economy even after they have lowered interest rates as far as they will go.

If lowering interest rates is like crack to the equities markets, then QE is an extra shot of meth. QE lowers the risk-free rate of bonds to the ‘zero-bound’ and sends investors scrambling to riskier assets in search of yield.

But, Bernanke’s plan worked. It saved the economy, and we learned our lesson, and would never do anything like this again.

If You keep Yellen at Powell, He Might Start Crying:

In December 2015, after 7 years of 0.0% interest rates and 3 rounds of QE, Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen raised interest rates for the first time since 2006. Over her tenure at the Fed, she raised rates from 0.0% to 1.5% from 2015 to 2017. When her first term was up, the Trump Administration contemplated renominating her, but eventually replaced her with Jerome Powell, a Republican candidate.

Unlike his predecessors, Powell does not have an academic background in academic economics. He spent the formative years of his career wandering around the magical world of Oz, looking for courage. Eventually, he found out from a guy who was lying about being a wizard, that he had courage all along. Predictably, that also turned out to be a lie.

After Powell began as Fed Chair, he continued Yellen’s work of raising rates. Because lower interest rates are conducive to economic growth, Presidents often want a Fed chair that will lower rates. In this sense, Trump was no different.

Trump approached the challenge of having a Fed chair that raised rates with the landmark quiet dignity that has become synonymous with his presidency. Powell increased rates 3 times throughout 2018 by a total of 0.75%. The stock market reacted negatively to the hikes, and Trump used increasingly strong language over Twitter to express his regret… distaste… and finally hatred for Powell.

When Trump began calling for his demotion or removal, Powell caved, reversed course, and started lowering rates. Not satisfied with Powell’s change in direction, Trump persisted until Powel agreed to restart QE in October 2019. The only explicable reason for Powell to do this was to appease the president and save his job.10

When COVID hit the market in March 2020, Powell reacted quickly, cutting rates to 0.00% and expanding the QE program. His quick reaction has been credited with the quick rebound in the market and economy since the peak of COVID.

Conclusion:

While Powell earned praise for his quick action during COVID, the rate cuts before COVID left the Fed with less room to maneuver during the pandemic, which meant that the Fed’s actions were quicker to expand the money supply than they needed to be. Appeasing the Trump Administration falls outside of the Fed’s mandate and is eerily parallel to Strong cutting rates in 1927 to assist England.

Powell has recently messaged that while the Fed plans to taper QE by the end of 2021, it will keep an eye on markets and back off if needed. Recent inflation readings are above the Fed’s target of 2% for the first time since 2008. Powell has conveniently labeled this inflation ‘transitory’ and pointed to unemployment levels of 5.4%11 as a reason for the Fed to remain accommodative.

However, the relationship between inflation and unemployment has decoupled in the last decade. The US has kept interest rates at historically low levels for 14 years, while both unemployment and inflation have remained low. This was made possible by using an influx of cheap imports from China as a source of deflation.

There is also reason to believe that it is unemployment not inflation that is transitory. Stubbornly high levels of unemployment could be a function of government stimulus which is scheduled to roll off in the fall of 2021. If that is the case, the Fed will be left with no Monetary Tools to use in case of another downturn, because cutting rates during an inflationary cycle could risk hyperinflation.

On the Fiscal Policy side, the Trump Administration passed $3.9T in stimulus during the height of the pandemic. Not to be outdone on handouts by Republicans, the Biden Administration passed $1.9T of stimulus after coming to office. Even though the later rounds of fiscal stimulus seemed less necessary (i.e., a third round of payouts to airlines that were no longer asking for it), both parties exhausted political and financial capital in order to pass their individual stimulus bills. As a result, if we are faced with another downturn, fiscal stimulus will be less available without a fight from increasingly alarmed congressional budget hawks.

With Monetary and Fiscal Tools likely tapped out, it will be harder to ‘make it rain’. If Greenspan is blamed for the 2007 recession because he kept interest rates too low for 3 years after the bursting of the internet bubble, then isn’t there increased risk from keeping rates low 12 years after the end of the recession in 2009 (10 years if you are counting before the pandemic)? Since Bernanke launched QE in 2008, the market is up ~350% (+200% if measuring against the pre-2007 recession highs).12 The risk of a significant market correction and a loss of confidence bleeding into the real economy is significant.

As Bernanke’s mentor Lil Wayne learned, the love of others from making it rain is ephemeral. Once you’re out of money for the night and the lights in the strip club come back on, you are just some asshole that referred to a room full of women trying to earn a living as ‘hoes’.

Sources:

The above article did not rely on first-hand sources. It was written using common knowledge about events as well as anecdotes, not conclusions unless footnoted, from historical accounts:

“Lords of Finance” by Liaquat Ahamed

“Firefighting” by Ben Bernanke, Timothy Geitner, and Henry Paulson

“A History of the United States in Five Crashes” by Scott Nations

“The Man who Knew” by Sebastian Mallaby

“Boom and Bust” by William Quinn and John D. Turner

“Hoover” by Kenneth Whyte

“Money Makers” by Eric Rauchway

“A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960” Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz

- I am just trying to make a point here… They are all nuts

- During the Pandemic, the US Gov made three rounds of Stimulus available to airlines. During Each round ~70% of the Gov money made available to airlines was through grants which didn’t need to be paid back, while ~30% was through loan facilities which would have to be paid back. Airlines took all three rounds of free grant money for ~$36bn, while only taking ~$1.5 of the loan money made available. If they really needed the money, they would have taken both the grant and the loan portion.

- Liaquat Ahamed, “Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World”

- This fact as well as most other facts about Montagu Norman and Benjamin Strong’s Relationship are from Liaquat Ahamed’s “Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World”

- Dow Jones Industrial Average is being used as a Proxy for the stock market.

- Hello, the second warranty on your vehicle is about to expire… Don’t hang up. My name is Killroy Notrobot. As you can guess from my last name, I am a tech billionaire who invented the internet test where you prove you are not a robot by selecting grainy photos…. Here’s a helpful hint, sometimes a bus is a car and sometimes it’s not. Also crosswalks and traffic lights are very loosely defined. Anyways, since selling my company, I have dedicated my life to calling everyone in America to warn them that the second warranty on their car is expiring. The only problem is that my voice sounds very robotic, which is also the backstory on why I invented the test in the first place. But, when everyone hangs up on me, it reminds me of my affliction, and I get depressed. So please, the next time I call you four times in a day, don’t hang up, stay on the phone, tell me about your day, give me your Social Security number.

- Represented by the Fed Funds Rate

- Sensing a question had been posed in this manner somewhere in the universe, Keanu Reeves woke up in a cold sweat shouting ‘Shoot the Hostage’.

- I’m not sure why, but Bernanke just looks like he owned a Zune and not an iPod.

- At the time Powell Lowered Rates in July 2019, US Unemployment was 3.7%, the lowest it has been since 1970. There was little to no justification for lowering rates at the time.

- July 2021 US Unemployment Data

- Using the IWM Russel 2000 ETF for this measure as the S&P 500 has become more tech weighted in recent years

Leave a Comment